A memoir about marriage, methamphetamine & mental illness

By Stephanie Rosenfeld & Luciano Colonna

Chapter One – His Past Was Behind Him

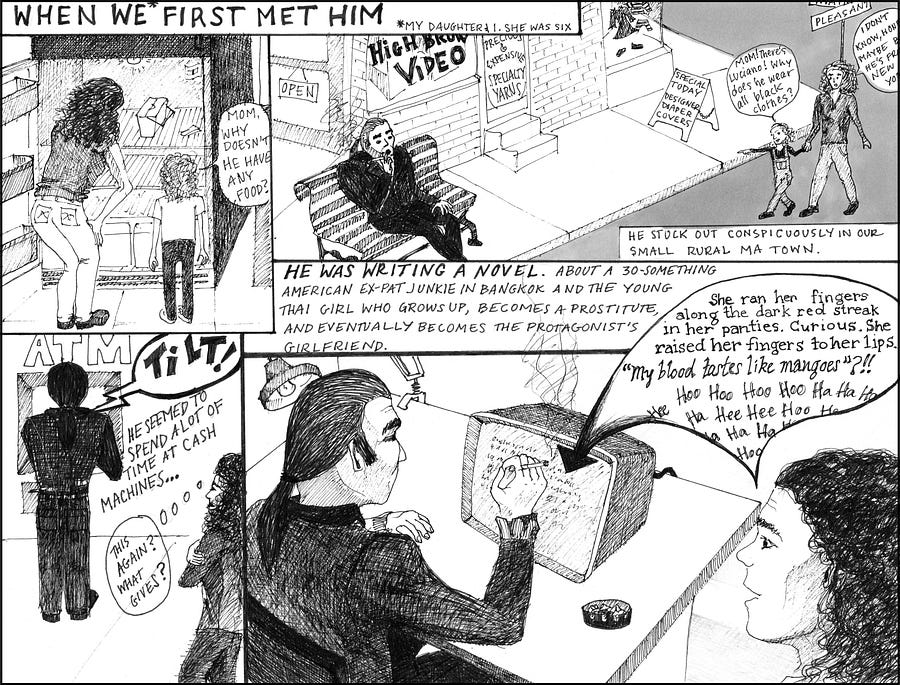

I met Stephanie in Northampton, Massachusetts, where I had moved from Los Angeles after spending a year there caring for a friend who was battling AIDS. After his death, I moved to his hometown, at the urging of his family, to regroup. I lived in a studio apartment above the town’s independent video store — the kind that had a designated Women Directors shelf and Be-kind, Rewind stickers on the cassettes, run by clerks who knew everything about film and would shame you over your rental choices.

I met Stephanie in Northampton, Massachusetts, where I had moved from Los Angeles after spending a year there caring for a friend who was battling AIDS. After his death, I moved to his hometown, at the urging of his family, to regroup. I lived in a studio apartment above the town’s independent video store — the kind that had a designated Women Directors shelf and Be-kind, Rewind stickers on the cassettes, run by clerks who knew everything about film and would shame you over your rental choices.

I had heard about Stephanie before we met. Mutual friends had described her as “smart, talented, beautiful and difficult.” I could tell who she was right away even though her back was turned toward me. She was with her six-year-old daughter (who would later say that she liked me because I looked a little like Tommy, the White Power Ranger), searching the Recent Titles section. I walked over to her and suggested she rent Household Saints. She gave me a polite Who-the-fuck-are-you? look, but checked out the video, asking the clerk — my dead friend’s brother — what my deal was. He told her my name, and that I was writer. She asked him if Luciano was my real name, and if I was a real writer. He told her that Luciano was the name written on my video rental agreement, and that I sat in my room and wrote all day, but he didn’t know what.

I began to pursue Stephanie with the same kind of relentless determination I had when I used heroin. I spent money on her that I didn’t have. I hung out in front of her house as if I was waiting to score, trying not to be seen, hoping she would come out so I could manufacture a casual encounter. I was thirty-eight years old and it had been five years since I’d used drugs. I was full of grace and felt I was finally ready to try having a long term, honest and monogamous relationship — with Stephanie. When I told her how I felt, she said no thank you — telling me she didn’t want to be anyone’s experiment.

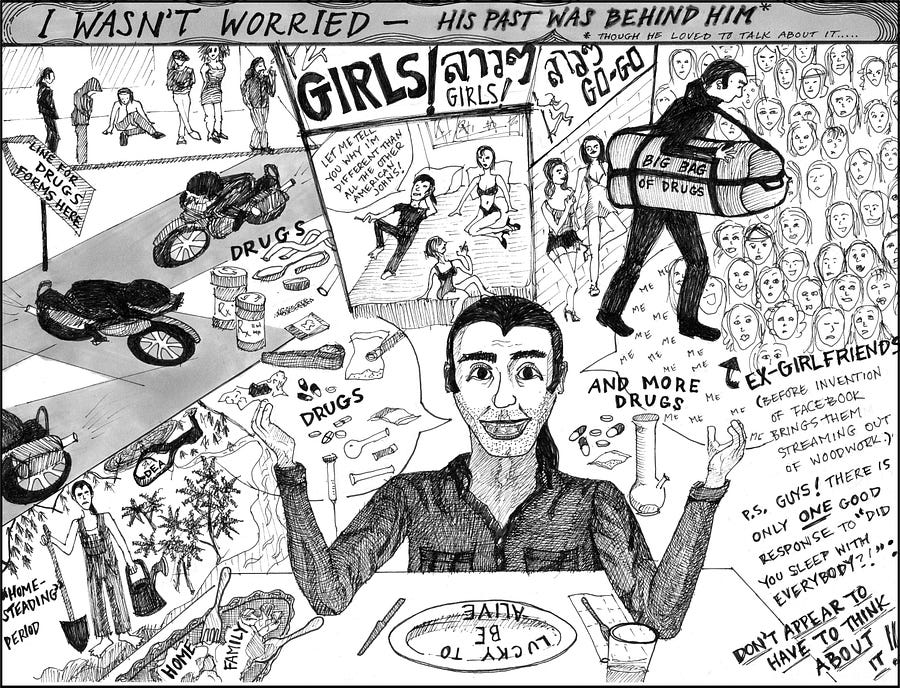

“You would have hated me if you’d known me back then,” Luciano would say, telling me stories of his drug-using days, and I’d agree: You’re lucky I didn’t meet that guy. I wouldn’t have looked at him twice. But that wasn’t the guy I’d met, and I did look at him twice. He was magnetic and funny and interesting and full of life. My daughter fell for him too: His manic need for an audience was perfectly fulfilled by the attention of a rapt five-and-a-half-year-old — Look! One of my arms is shorter than the other! They call me Mr. Cyber! This is the song that never ends…!” — and she was smitten by the fact that he looked like the White Power Ranger.

“You would have hated me if you’d known me back then,” Luciano would say, telling me stories of his drug-using days, and I’d agree: You’re lucky I didn’t meet that guy. I wouldn’t have looked at him twice. But that wasn’t the guy I’d met, and I did look at him twice. He was magnetic and funny and interesting and full of life. My daughter fell for him too: His manic need for an audience was perfectly fulfilled by the attention of a rapt five-and-a-half-year-old — Look! One of my arms is shorter than the other! They call me Mr. Cyber! This is the song that never ends…!” — and she was smitten by the fact that he looked like the White Power Ranger.

Luciano was determined to make me his girlfriend — though, at the time, I was still technically married and I had a boyfriend, who everyone was convinced was just a gay friend I’d brought back with me from my recent stint in culinary school in San Francisco.

“I’ve always wanted a smart, beautiful, sexy, brunette,” Luciano would say, making his case for why I should be with him. He seemed puzzled by my non-enthusiastic response. “I’ve never been in a committed, monogamous relationship before,” he said, one day. “I’d really like the chance to try it with you.” Again, puzzled by my response: “Is that supposed to sound like a qualification to me?” I think I said.

Though we made his words into a joke, back then, twenty years later, I’d look back and see them in a different light. Other things I would see in a new light: When I met Luciano, he was selling off all his possessions, one-by-one. I’d never seen this before — even though I’d grown up in a poor family, this wasn’t a money-making strategy anyone I knew resorted to, especially in those pre-eBay days. Also, he was always slipping off to make phone calls from phone booths, and he made an awful lot of visits to cash machines. I wondered about this, but only idly, and in the end just chalked it up to the general mystique of Luciano: He’d been a lot of places and knew a lot of people; he made his money in ways completely unfamiliar to me, but what did I know? — I was kind of a bumpkin. And, anyway, he always seemed to come out okay, to be in an upbeat mood, to come up with enough cash for our next take-out Chinese dinner.

When I used, heroin was my drug of choice. I also had a short list of safety-drugs that included cocaine and pills. Alongside my drug use was a compulsion to spend my time moving around in the most sordid and disreputable life I could find, the type of scene that has become a cliché, the narrative of male writers without talent. I’ve been around a number of old timers who like to tell young users about the good old days, when the drugs were stronger, cheaper and easy to score. But that’s not the way it was.

When I used, heroin was my drug of choice. I also had a short list of safety-drugs that included cocaine and pills. Alongside my drug use was a compulsion to spend my time moving around in the most sordid and disreputable life I could find, the type of scene that has become a cliché, the narrative of male writers without talent. I’ve been around a number of old timers who like to tell young users about the good old days, when the drugs were stronger, cheaper and easy to score. But that’s not the way it was.

In the days before cell phones and pagers, I would take a subway up to the Bronx, down to the Lower East Side, or out to Brooklyn. I would get off the train and walk toward the dope spot, which might have been an abandoned building, a park, a bodega, or laundromat — or sometimes, literally, a hole in a wall. I would stand in a long line of junkies next to a long line of crack heads with a twenty squeezed tight in my hand, slowly moving to the front of the line, hoping to get there before the dope was gone or the police showed up.

One way or another I would get my dope and take it to a shooting gallery and pay a couple of dollars for the privilege of using their spoon and some clean water. Works were extra. Once when I was using on the top floor of a partially burned-out building in Hunts Point, a woman overdosed and died after shooting Fentanyl. Two guys picked up her body and threw it out the window. No one stopped them. Then there was the time I saw some fourteen or fifteen year old dealers make a crackhead blow a pit-bull for a five-dollar rock. Heroin cost ten dollars and was stamped with brand names like D.O.A., Poison, Tango, and Cash. AIDS was on everyone’s mind. Nobody knew that they had Hepatitis C.

The money I made from dealing was enough to pay for both my rent-controlled apartment in New York and a clean room in Bangkok. You know you’re a dope fiend when you smuggle heroin into Thailand, something I did repeatedly during the 80s. I couldn’t risk being stuck anywhere without dope in my pocket.

I loved Bangkok. I lived there for a while, strung out, taking photographs of lady-boys and living with a hooker. I loved the traffic jams, dive bars, working girls, food, and the cheap heroin. I believed that I was doing something very important back then, something interesting and significant— something that I believed would go on forever. The only thing that made me leave was the sight of my Thai girlfriend wiping a small amount of China White into the gums of her new baby boy to make him stop crying and go to sleep.

In the beginning, I told myself that every shot would be my last one. Then one day while taking the subway up to the Bronx, I got up from my seat on one side of the train and walked over to the other side. And just like that, with that movement, I admitted to myself that I would always be a junkie and that all I needed to do was to make enough money to pay for my drugs. I spent most of the rest of the decade trying to find drugs and trying to find a vein.

I wasn’t impressed, but I also wasn’t worried: All of that was behind him. He was a teetotaler when I met him, five years clean after a decade of heroin addiction, and proud of his sobriety. He told me the story of his hard-fought battle to get clean, expressed pride in his new-found health, showed me his five-year chip. He was glad to be living a saner existence, glad to have finally gotten his act together, to have found some greater purpose beyond the endless cycle of getting drugs, getting high, getting money for drugs, getting more drugs.

We hung out, fell in love, became a couple, then a family. I felt we were well-matched in some important ways. We shared a mutual cynicism that made us laugh, a lot. We’d both had unconventional upbringings marked by instability and trauma, which made us feel like members of the same secret club. We’d trade stories about our fucked-up childhoods, but I knew he had me beat by a mile: Machine-guns under the couch cushions and a secret second family made my wooden-spoon beatings, verbal eviscerations, and parental abandonment seem humdrum. To me, it felt as if our damage meshed, and made us compatible — that it made us good partners, in many ways. We were protective of each other, aware of each other’s vulnerabilities.

My story of our marriage was: We were two people who had overcome some significant damage in our lives, suffered setbacks, and failed to jump onto conventional paths, but, luckily, had found each other; and together, we were going to create something good. We’d sit at the dinner table planning our future together. We were counting on being late-bloomers.

This Is Your Marriage On Drugs is a memoir about marriage, methamphetamine and mental illness. A collaboration between Luciano Colonna and Stephanie Rosenfeld, please visit www.stephanierosenfeld.com to view additional short stories, essays and novel excerpts by Stephanie.