A memoir about marriage, methamphetamine & mental illness

By Stephanie Rosenfeld & Luciano Colonna

Chapter Eight – He’s Got A Problem

I started working in Harm Reduction shortly after the death of my friend Tim. I’d met Tim fifteen years earlier, in Santa Cruz. Tim was good looking, charismatic, a cheerleader to your dreams and schemes. He was someone you left your boyfriend for, flunked out of college or lost your job to be around. Ours was a singular friendship, the kind you’d do anything to have again when you find yourself old and struggling with loneliness.

I started working in Harm Reduction shortly after the death of my friend Tim. I’d met Tim fifteen years earlier, in Santa Cruz. Tim was good looking, charismatic, a cheerleader to your dreams and schemes. He was someone you left your boyfriend for, flunked out of college or lost your job to be around. Ours was a singular friendship, the kind you’d do anything to have again when you find yourself old and struggling with loneliness.

When Tim and I met, we were both in long-term relationships that we were having a hard time extricating ourselves from. Our girlfriends were similarly jealous, unhappy, and highly critical, we discovered, when we compared notes. I can’t remember exactly how it happened, but, shortly after meeting, the four of us broke up and switched partners. Tim and I noted the transition by eating psilocybin mushrooms and hiking up to the UCSC campus with our guitars. There, with a psychedelic view of the Pacific Ocean, we played and sang David Lindley’s Your Old Lady (Sure Looks Good to Me), and said things too corny to write, here, about staying friends forever.

Tim was vocalist, front man, and leader of a band called The Delusions. The first time I saw The Delusions play was at Van Ness house, a beat up Victorian in Santa Cruz that was home to the band, their roommates, and a scandalous Jacuzzi. The band was terrible — out of tune, out of rhythm, and out of it, that night. They sounded like they were playing toy instruments. I returned to Van Ness the next day and joined up.

We were all pretty bad musicians, but as the front man, Tim’s lack of talent shone brightly under the spotlight. His drumming was actually much better than his singing, but he couldn’t bear playing to our backs — he had to be up front; so the drumming was left to Blake, an unreliable coke fiend, a man-child who spoke in baby-talk when arguing with Tim about his lack of commitment, something that would always trigger Tim’s gag reflex.

As someone who’s been around professional musicians all my life, I knew just how bad we were, but that was never a problem, since people weren’t coming for the music — they showed up for Tim. From the time he knocked out two of his teeth, screaming into his microphone when we opened up for Pearl Harbor and the Explosions, to the time we premiered his Rock Against Reagan anthem, “Ronny is a Homo” to an angry LAMBDA benefit audience, Tim’s charisma was always the main draw.

The truth is, we wrote better than we could play. Much better. I wrote a lot of our songs, and I think they were actually pretty good. When Stephanie heard me sing them, she said, “They sure do have a lot of words in them,” and pointed out their manic quality. Our set lists were cries for help, wrong numbers and Dear John letters.

Set List. Sound of Music. Turk Street, SF 12/31/83

A Bad Day in Sunnyvale

If You Cut Me Off at the Knees

I’m Sitting in Las Vegas, Waiting for a Bus

I’ve Got a Problem

Etc.

Later, as soon when Callie was old enough to be interested in playing music, I taught her some of the Delusions’ old songs and we’d play and sing them together.

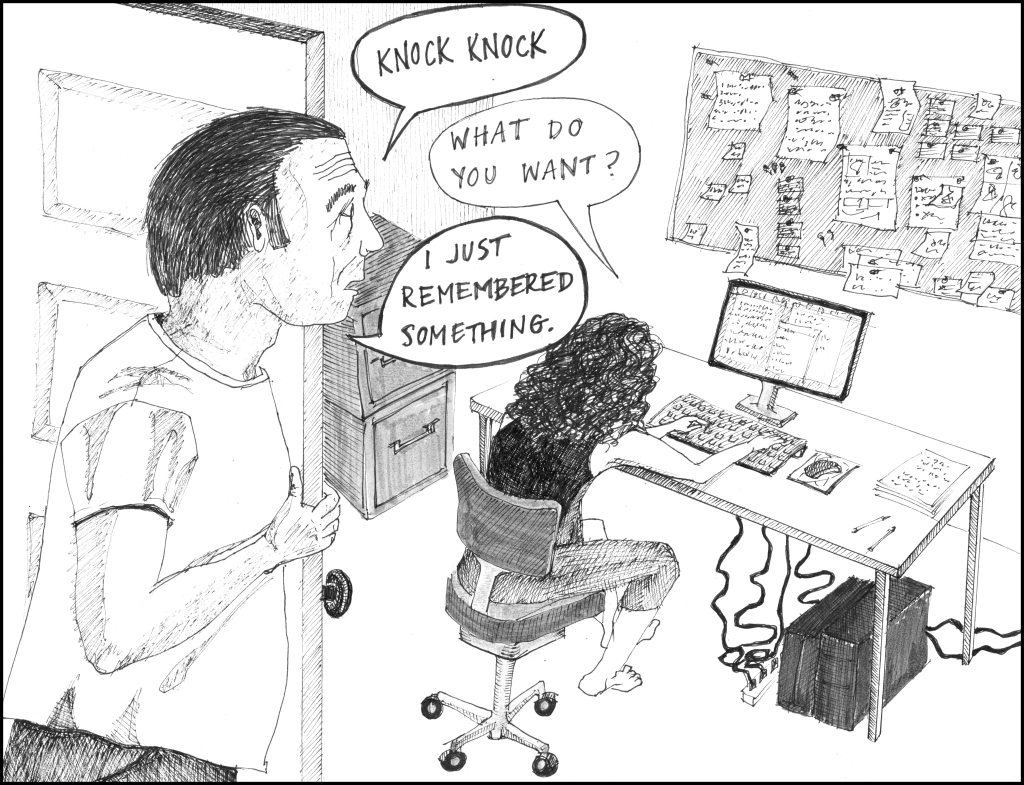

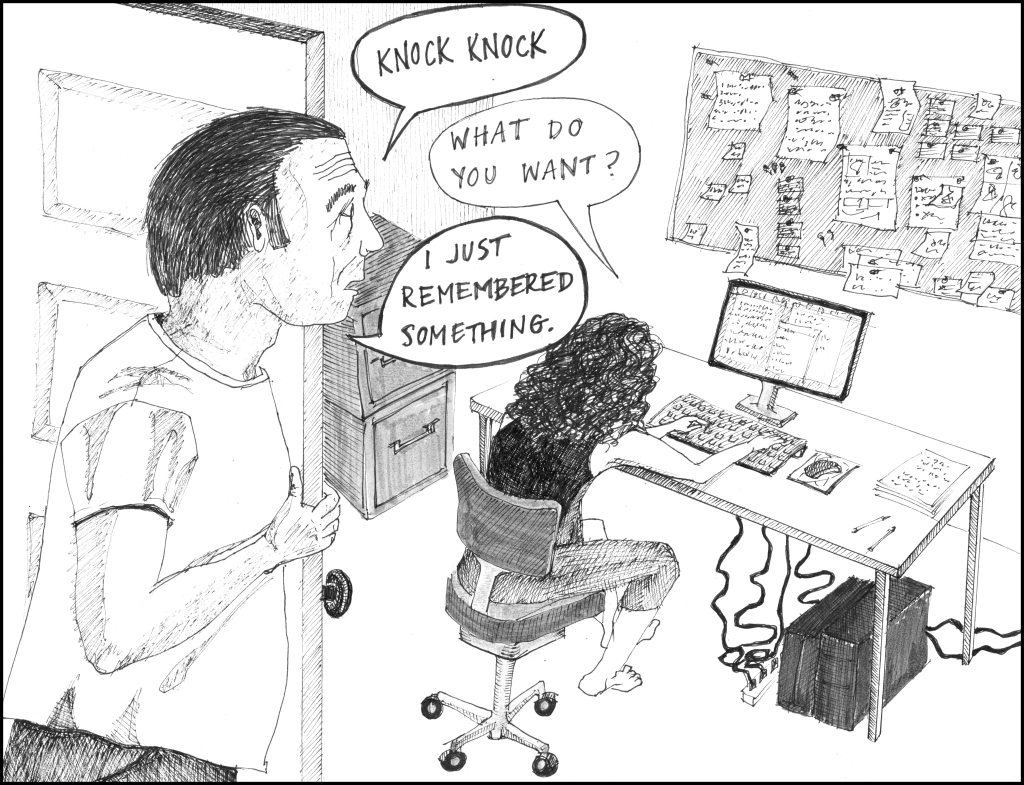

STEPHANIE: Can I ask you a question?

LUCIANO: What?

STEPHANIE: Don’t get mad. But, did everything you and Tim did, together, incorporate drugs?

LUCIANO: No!

STEPHANIE: I mean, that’s not supposed to sound judgmental. But it just seems like every story you tell starts out with the two of you being really, really high, or doing magic mushrooms, or dropping three hits of acid in the parking lot before you start out. I’m just trying to get a picture.

LUCIANO: Well, it’s not true!

STEPHANIE: Why are you getting mad? I’m just asking!

LUCIANO: I just don’t like the way it sounds! I mean, yeah — we did drugs. But that’s not what I was writing about! It wasn’t a problem, back then: We were just young kids, having fun. Having a lot of fun. It was a good part of our lives. And, yeah, getting high was a part of it! But we weren’t “doing drugs.”

STEPHANIE: So, mushrooms and LSD aren’t drugs?

LUCIANO: Right. Or pot.

LUCIANO: What, Stephanie?!

STEPHANIE: I’ve just never heard you say that before. And I’m not sure I agree — that pot’s not a drug.

LUCIANO: It’s not a hard drug.

STEPHANIE: Well, yeah. But are you saying that if something’s not a hard drug, it doesn’t count as a drug?

LUCIANO: Yes.

STEPHANIE: Huh. Oh, BTW? I’m not even sure we can say pot. Not if any young people are reading this, anyway.

LUCIANO: Why?

STEPHANIE: They just laugh at you — they all call it weed. OH MY GOD! Did I just know something about drugs that you didn’t?! Anyway, one reason I was asking was: If anyone from Tim’s family reads this, are they going to be surprised about the drug use? Or upset?

LUCIANO: No. Tim didn’t have a drug problem. I was the one with the drug problem.

STEPHANIE: I thought you said your drug use wasn’t a problem.

LUCIANO: Yes! No! I mean, yes, later! But not then! We were all just having fun!

STEPHANIE: So you said. So, you weren’t using heroin, in Santa Cruz?

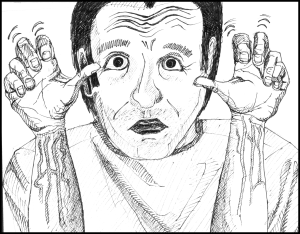

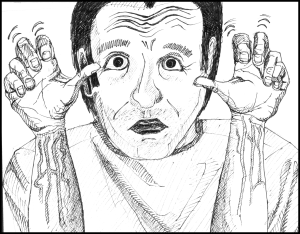

LUCIANO: Yes! No! My God, Stephanie! You want me to SIT DOWN and make a chronology of my drug use??!

STEPHANIE: Uh, yeah — kind of.

LUCIANO: But that’s not what I’m writing about! I’m writing about my friendship with Tim! And, yeah, we smoked a lot of pot! Tim didn’t use heroin. He smoked pot. He loved to smoke pot.

STEPHANIE: Weed.

LUCIANO: We smoked a lot of weed — nah, I can’t: We smoked a lot of pot together. So, yeah, we were pretty much always high.

STEPHANIE: But not on drugs.

LUCIANO: You’re infuriating, Stephanie.

When the band moved to San Francisco, Tim and I went with them. There, too broke to pay our rent, or buy food or guitar strings, we had no choice but to look for jobs. Having no real work experience, our choices were limited. For a while, Tim sold encyclopedias door to door and I landed a job writing trivia questions for computer games. Working changed little, as we spent pretty much everything we made on girlfriends and drugs. In the end, Tim sold a few sets of encyclopedias to his mother and grandmother, and I returned to selling drugs.

A few years later, the band broke up, and most of The Delusions found jobs or went on to graduate school. Tim moved to New York to make it as an actor, and I as an addict. He landed the lead in a Caramello candy bar commercial, and began working in off-off Broadway theater. I used and sold a lot of drugs during that period, occasionally scored the music for Tim’s plays, & traveled back and forth between apartments in New York and Bangkok.

I was crushed when Tim told me he had tested positive for HIV. He was thirty-two years old. It was 1992, and the diagnosis was a death sentence back then. With effective combination antiretroviral treatment years away from being developed, the progression of the disease from diagnosis to full-blown AIDS to death was often fast. Most of those I had known who’d contracted the virus were dead.

That Tim was sexually attracted to both men and women was no surprise to me — I had always envied his ability to act on his impulses despite his lurking WASP background. He believed that he’d most likely contracted the virus when we were living in San Francisco, a theory that made sense, timing-wise. But it could just have easily been in New York, as both cities had the kind of vibrant, libertine scenes Tim liked to dip his toe into.

“I have to say this,” I told him — needing to get it off my chest in that terrible moment. “What the fuck, man?” As in: Why hadn’t he been using condoms? “What were you thinking?”

“I know,” he said.

Yes, it’s ironic that I, of all people, would challenge anyone about risk-taking. I had put myself at risk ad infinitum, and sadly, I would do so again, years later, despite the death of my best friend. Of course, I was being rhetorical when I asked him what he was thinking: It was a reaction to our suddenly losing control of our destiny. It was unfair. Not just that Tim’s life was going to be cut short, but that he’d contracted HIV and I hadn’t.

When I met Luciano, his friend, Tim, had just died from AIDS. Luciano talked a lot about Tim: The friendship he described sounded close, intimate, and honest. I didn’t know Luciano well enough, then, to know how significant that was.

And though I understood the tragedy of Tim’s death in its bigger sense, it took me a while — like, twenty years — to understand more fully what the loss had meant to Luciano.

Maybe that was because of the way Luciano put his memories of Tim in the form of funny, entertaining stories. The time, just after they met, that they did mushrooms and switched girlfriends. The time they went to Disneyland and dropped three hits of acid in the parking lot and Tim had a bad trip on Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride and lost it completely in the Country Bear Jamboree, and they had to wait till everyone left the park, because they couldn’t remember where they’d parked their car. Or, maybe it was because we were both self-absorbed, focused on our courting — Luciano striving to impress and entertain; me only half-listening to the parts that weren’t about me.

It took me another few decades, obsessively going over all I knew or thought I knew about Luciano, trying to put together a story I could understand about all that had happened — his relapse, and his leaving — to realize that beneath the stories lay a bigger loss than I had ever considered.

One opinion I had, that only grew stronger over time, was: Luciano was weird about friends.

On the one hand, it was kind of awesome how many people he’d known, been close to, lived with, traveled around with, traveled to see, done drugs with, fucked. He had endless stories, spanning multiple personal epochs, and a vast cast of characters that populated them: The Santa Cruz friends, the New York crowd, the “homesteading” crew, the “business associates,” the endlessly recombining housemates, the Asian girlfriends, the European girlfriends, the American girlfriends, the Bangkok lady-boys; the Deadheads who’d meet up in different cities for concerts, or sometimes “go on tour” together, with the band. And he talked a lot about how important they’d all been to each other.

But even though the majority of these people were still alive, and many of them still got together for visits and events and reunions, and wanted Luciano to join, he wouldn’t pick up the phone when they called. He wouldn’t go to the reunions; he rarely let anyone know when he was in their city for work; he never accepted the invitations to visit, or invited any of them to visit us. When I’d ask him why, he’d just respond with irritation and deflection.

The only person I ever met, for a long time, was Jennifer. We stayed at her apartment, once, early on, when we went down to the City.

Jennifer was Luciano’s oldest friend, and I knew she’d helped him through some hard times. Practical-minded, outspoken, not a drug-user herself, she hadn’t been a big fan of him as a junkie, and he told many stories of her persistence at trying to help, persuade, and force him get clean. She seemed like a grounding presence, for him, and I liked the thought of that; and also, as time went on, the knowledge that there was at least one other person in the world who wasn’t a pushover for his bullshit.

I liked the way they talked to each other. Like a bickering couple, only without the stakes. She’d challenge him about something — often in foul language — and for some reason, he didn’t respond abusively or explosively, like he would have if I’d said the same thing.

I was glad when Luciano finally introduced me to Jennifer: I’d brought a daughter and a bunch of friends into our relationship; I was happy at the thought of our world expanding to include some of his “family,” too. I was disappointed when I didn’t see Jennifer again for ten years.

STEPHANIE: How did Tim feel about your using heroin?

LUCIANO: What do you mean, how did he feel about it?

STEPHANIE: What do you mean, what do I mean? He was your friend. He must have had an opinion. It probably affected him. Was he just fine with it? Was he concerned? Did he want you to stop? I’m sorry — what’s wrong with that question?

LUCIANO: I just don’t know why everything has to be so focused on my drug use!

STEPHANIE: I think it’s a pretty legitimate question — to wonder about how your drug use affected your close friends.

LUCIANO: It didn’t affect him! He didn’t see it as a problem! Anyway, that wasn’t what I was writing about! You told me to write about Tim! You didn’t say this was going to be all about drugs! I’m just following your instructions!

STEPHANIE: No! That’s not how this works! I told you to write about Tim because you made the link between his death and your going into Harm Reduction in the very first sentence of this chapter, if you recall; and I said maybe talk about that, a little. But, by all means, write what you want to write! Tell it your way: You’re in New York, doing drugs, not doing drugs — it’s inconsequential; Tim dies; you go into Harm Reduction. Yawn.

LUCIANO: You’re so infuriating, Stephanie.

While I’d been chipping heroin for a while, it wasn’t until that time in New York that I developed a full-blown habit. I made periodic attempts to get clean during that time — probably about twenty or thirty over a six-year span — relapsing over and over again. My friends were concerned: Both Tim and Jen would be really happy, each time I stopped using. I wasn’t a very good friend when I was on heroin. I was really unpleasant to be around, and I’d disappear a lot , because I was hanging around with other people — doing heroin with my heroin friends.

It wasn’t very hard to hide my problems from my family, when I was using. When I did see my mother and father, I told them my skeletal appearance and pallor were the results of a struggle with malaria. My having to leave in the middle of a visit to their house in New Jersey to return to the City during a snow storm on Christmas Eve, to cop, would be explained with a long, drawn out lie about volunteering in a soup kitchen. Nodding out on their couch while smoking was the result of my working too hard.

The one conversation we had about my drug use, when I finally decided it was time to tell my parents about my addiction, after celebrating the one-year anniversary of getting clean, went like this:

“I don’t actually have recurrent malaria. I’ve been using heroin for years. But I’m clean and sober now. I’m doing great. I thought you’d like to know.”

“That’s good, man. You need to stay off of that stuff,” was my father’s response, in its entirety.

My mother was more surprised and disturbed. What drugs had I been using? she wanted to know. Not wanting to highlight heroin again, I said, “All of them.”

She got an anguished look on her face.

“Did you use hashish??” she said. “Please tell me you never used hashish!!”

I’m not sure where she’d developed her terror of hash. Maybe she’d seen the movie Reefer Madness as a teenager.

“No mom,” I lied, just to make the conversation stop. “I managed to stay away from hash.”

“Thank God!” she said. It would be twenty years until we discussed my drug use again.

My friends were harder to lie to. So instead, I stayed away from them. It was easier with some than others. Jennifer, for example. Jen simply refused to let me destroy myself in peace. Jen watched me use, kick, relapse, and lose my mind so many times over the years, neither one of us would be able to count. I subjected Jennifer to a lot: There was the time I jumped out of a moving taxi on our way to dinner, when, after earnestly promising her I was going to get clean, I suddenly decided I needed to get high. Holed up in my apartment, I would yell and throw things at her voice, on my answering machine: “I know you’re in there! Answer the phone! Looch, pick up! Pick up! Pick up! Pick up! Pick up!”

And there was the time I relapsed the same day I completed the Mexican detox. After checking into a sleazy Holiday Inn in downtown LA, I began to panic about the reality of what this relapse might mean: Would I have to go straight back into detox, which had just about killed me? — which resulted my using my three-day stash of heroin in a single shot. Very high, paranoid and manic, I hallucinated a giant beaver standing on its hind legs at the foot of the bed. Freaked out, I called Jen for help. But, unable to talk, I just sobbed into the phone. Her voice was equal parts concern, exasperation and rage as, despite my having called her, I refused to reveal my location.

In 1987, when I was wasting away in Bangkok from a diet of heroin, benzos and Mekong Whiskey, she flew me back to New York and nursed me back to health in her home in the Hamptons, though I relapsed again, not long afterward. And twenty-five years later, when I was addicted to meth and homeless in Phnom Penh, she got herself a visa, in preparation to fly to Cambodia to rescue me. I told her I would fly home on my own if she bought me a ticket.

IF YOU DON’T GET ON THIS FLIGHT I’M FINISHED WITH YOU! she emailed.

Tim was actually really important in my recovery.

I was back in New York, after Sierra Tucson, doing the hard, boring work of recovery. Unemployed, with little to do, I saw every film I could, moving across the city from theater to theater, until finally ending up in the almost empty movie theaters in and around Times Square, which played classic Kung Fu movies, horror films and of course, porn. When I wasn’t at the movies or seeing my therapist, Babette, or waiting for [REDACTED] to give me the job he had promised me if I “ever stopped getting high,” I was attending one of the thousands of 12-step meetings that met throughout the city. I went to both NA and AA meetings, but I preferred AA because the meetings were shorter.

Determined to stay sober, this time, I did as I’d been instructed in rehab, attending ninety meetings in my first ninety days of sobriety. I found a sponsor — I knew he was the one for me when I learned he’d served three years in Attica for “Robin Hood” crimes (he’d mug the rich and then share his loot — minus drugs and expenses — with some of the homeless who hung out in Tompkins Square Park) and had been arrested when the police showed up while he was giving CPR to the victim of one of his stick-ups who’d had a heart attack, trying to find his wallet.

Predictably, much of AA was a problem for me. I detested the platitudes and slogans, the Christian messaging, and the hypocrisy; I didn’t like the miniature daily affirmation books, and I hated it when we all held hands at the end of meetings and shouted, “Keep coming back, it works if you work it!” I had no patience for the older men who hung out in the back of the rooms and made comments to one another about “13th-stepping” the young female newcomers. And the drug- and alcohol-free activities (“sober dances,” “sober bowling,”) gave me a sense of dread about the life in front of me.

Upon making it to three months clean I received a red coin the size of a poker chip, recognizing the anniversary of my sobriety and was invited to share my story at a meeting. After my twenty-minute testimony about a lifetime of drugs and bad choices, my sponsor told me that I had to do another “ninety in ninety.” My attendance at AA quickly dropped from daily to weekly. I’m sure I would have dropped out completely, if not for Tim.

Looking for a sense of control after his diagnosis, Tim had switched to a healthier diet, stopped drinking alcohol, and began using condoms. And despite his chronic pot smoking we began going to 12-step meetings together.

Tim said that he attended the meetings for the anonymity and the hope. He also went because he knew that I was more likely to attend with him by my side. He shared about being afraid and about stigma and the unknown. He made a lot of bad jokes. When he cried, many in the room would cry along with him. After the meetings, women would flock to him and slip him their numbers on matchbooks and meeting schedules. He was often high.

Though I had reached the limits of my tolerance for AA meetings by then, I kept going because I wanted to be with Tim as much as possible. I know that Tim’s presence, along with the routine of attending AA meetings and the support of its members, were a big part of my being able to stay clean, back then.

At some point after his diagnosis, Tim returned to stay with his mother in Santa Monica. When he started to develop the first symptoms of full-blown AIDS, he called me in New York and said that it was time for me come.

I’m really grateful that I wasn’t using drugs when Tim was dying. I’d finally cleaned up, and that was really important: If I hadn’t, there’s no way I could have done it — that I could have been there for him. Like, literally, I would not have shown up. Everyone was amazed that I did, including Tim and me. We talked about it: I can’t believe you’re doing this, he told me, laughing, then starting to choke, as I cleaned his tracheotomy tube.

Tim was sitting up in bed when I walked into his hospital room. He was about to start chemotherapy and was in good spirits. We joked (How did you manage to convince your mom that you’re Haitian?) and talked about the seriousness of the situation (Fuck. AIDS. Fuck.).

All the rooms in the AIDS Ward were singles and all were full of men in their twenties and thirties. So close to West Hollywood, many were quite handsome. I slept on a small pull-out bed that was reserved for family members. There was a shower I could use and a family room to hang out in when Tim had visitors. I’m not sure how long I stayed in there — it might have been a month or longer. Tim developed a brain tumor, went through a round of chemo, had a tracheotomy, and began radiation treatment. I became friendly with a few of the other patients and their families.

When Tim was released he went back to his mom’s house where a nurse was hired part-time.

Next came six months of vigils and comebacks. Tim never caught a break. The moment one emergency was brought under control another would pop up. Rubber cloves, morphine drips, catheters, sipping cups, wasting, cancers, thrush, neuropathy, night sweats. More radiation treatments. Family members flying back and forth from the East coast; friends sleeping on mattresses. A caring, Christian nurse who tried to convert Tim during the shifts when we just couldn’t stay awake any longer. Family and friends were called and informed “It looks like this is it,” only to watch Tim sit up during an opiate-induced coma to announce he was hungry.

One day, after returning from a two week trip back to New York, I walked into the house to find Tim sitting at the dining room table eating a bowl of soup.

“Where have you been?” he asked me angrily.

“Huh?”

“I asked you to come out here months ago!”

The radiation treatments had wiped away much of Tim’s recent memory. For him, I was just arriving. And, though I was glad that he couldn’t remember what he’d been through, I was also pissed that he didn’t know I’d been there with him all along.

Tim died in 1994. He was 36 years old.

Bruce, Melissa and I had made the arrangements, months before he died, for Tim’s body to picked up and taken to be cremated. A few hours after Tim’s body was taken from the house his mother asked us for the number of the crematorium. None of us could remember its name, number, or address. We spent the rest of the day searching until we found him. Memorials for Tim were held in LA and Northampton. Tim left me his guitar in his will. During one of the memorials I found that out that the guitar wasn’t his — Tim had borrowed it from The Delusion’s bass player, who wanted it back.

Beyond enjoying Luciano’s fondly-recalled memories, I really didn’t think too much about Tim, till many years later — till after Luciano had relapsed and washed up on my doorstep with nothing left in the world except a headful of residual meth psychosis, a death wish, and an insurmountable case of shame.

In one of our conversations — all of which were hard and sad and tense and fraught, during that time — Luciano said, “I think maybe Tim’s dying was the worst thing that ever happened to me.” And, “If Tim hadn’t died, maybe things would have been different.” I asked him what he meant, but he couldn’t really (or didn’t want to) say.

I wonder if that sounds self-absorbed — Luciano putting Tim’s death in terms of how it had affected him. Because I thought it, too — newly, in that moment: Aside from the other reasons that Tim shouldn’t have died: No one should die that young, and no one should die of AIDS; and his death had caused his family and friends immeasurable pain , Tim shouldn’t have died because Luciano’s life had definitely been the worse for it. And the friendship had proved irreplaceable.

If Tim hadn’t died, maybe they would have continued to grow up together. Maybe Luciano would have had someone he could have been honest with about his mounting troubles and secrets, someone who might have noticed his escalating prescription drug abuse. Someone who really knew him, whose opinions he respected as much as his own, who he couldn’t bully or yell at, and who wouldn’t just let him disappear.

Someone who might have said What the fuck, man? when he decided to start using meth.

Because, though there were many, many people who cared about Luciano, both from the past and, later, from his new career, he was never accountable to anyone. Not to Jen, not to me, not even, ultimately, to himself, I don’t think.

Luciano always left himself a loophole: Not just the disappearances, but the periodic acts of self-destruction, so forcefully-perpetrated and over-the-top that they almost seemed designed to make people throw up their hands and say, I give up! That’s just Luciano! — maybe so he could keep up the fiction that his self-harm wasn’t hurting anyone else.

If Tim had lived, I like to imagine that their friendship would have lasted, and would have stayed, for the most part, fun. And that even when sharing his problems, admitting his fears, processing through the shit of grown-up life felt about as appealing to him as sober bowling, the friendship would have been important enough for Luciano to keep coming back to — would have been a path through the hard parts, and would have helped him to not lose his way.

Looking around, various places, in preparation to write this section, I found something. A picture, on Jennifer’s Facebook page. I’ve seen it, here, too, in physical form in our house. It was taken by friend of theirs from the Dead days, Jay Blakesberg, now a San Francisco-based photographer and filmmaker.

I asked Luciano about the story behind the picture.

“When Tim was sick, we started doing things with him whenever we could. Parties, trips, shows. This was when the Dead played Las Vegas. We all met up there — Tim came from LA, the rest of us came from New York. We had free tickets and backstage passes, and we stayed in this good hotel. Tim and I had a fancy spa treatment together; we worked out together; we went to the casinos. The Dead played three shows and we went to all of them. It was a lot of fun.”

STEPHANIE: Can I ask you a question?

LUCIANO: What?

STEPHANIE: Were you high?

LUCIANO: OH MY GOD, STEPHANIE!

STEPHANIE: I know, I know — but I mean, just because, look at Tim, in this picture. To me, that looks like someone who’s either really high, or maybe someone who’s sick.”

Tim, Luciano, Jennifer and Lesly. Backstage at the Silverdome. Las Vegas, 1992

—

LUCIANO: You know what, though? Actually, we weren’t high, in that picture. I just remembered. I was clean and sober, by then. We didn’t do any drugs on that trip. That’s the reason Tim and I worked out together: We never would have worked out if we’d been doing drugs!

LUCIANO: What?! I’m sorry, Stephanie! I didn’t remember till right now! We do look high in the picture, though, don’t we? But I guess that’s just because we were happy. It was a great time. We were all really, really happy.

I started working in Harm Reduction shortly after the death of my friend Tim. I’d met Tim fifteen years earlier, in Santa Cruz. Tim was good looking, charismatic, a cheerleader to your dreams and schemes. He was someone you left your boyfriend for, flunked out of college or lost your job to be around. Ours was a singular friendship, the kind you’d do anything to have again when you find yourself old and struggling with loneliness.

I started working in Harm Reduction shortly after the death of my friend Tim. I’d met Tim fifteen years earlier, in Santa Cruz. Tim was good looking, charismatic, a cheerleader to your dreams and schemes. He was someone you left your boyfriend for, flunked out of college or lost your job to be around. Ours was a singular friendship, the kind you’d do anything to have again when you find yourself old and struggling with loneliness.

One opinion I had, that only grew stronger over time, was: Luciano was weird about friends.

One opinion I had, that only grew stronger over time, was: Luciano was weird about friends.

While I’d been chipping heroin for a while, it wasn’t until that time in New York that I developed a full-blown habit. I made periodic attempts to get clean during that time — probably about twenty or thirty over a six-year span — relapsing over and over again. My friends were concerned: Both Tim and Jen would be really happy, each time I stopped using. I wasn’t a very good friend when I was on heroin. I was really unpleasant to be around, and I’d disappear a lot , because I was hanging around with other people — doing heroin with my heroin friends.

While I’d been chipping heroin for a while, it wasn’t until that time in New York that I developed a full-blown habit. I made periodic attempts to get clean during that time — probably about twenty or thirty over a six-year span — relapsing over and over again. My friends were concerned: Both Tim and Jen would be really happy, each time I stopped using. I wasn’t a very good friend when I was on heroin. I was really unpleasant to be around, and I’d disappear a lot , because I was hanging around with other people — doing heroin with my heroin friends.